Tribal Verse Summary and Explanation

CBSE Class 11 English (Elective) Essay Chapter 4 – Tribal Verse Summary, Explanation along with Difficult Word Meanings from Woven Words Book

Tribal Verse Summary – Are you looking for the summary, theme and lesson explanation for CBSE 11 English (Elective) Essay Chapter 4 – Tribal Verse from English Woven Words Book . Get What is a Good Book? Passage summary, theme, explanation along with difficult word meanings

CBSE Class 11 English (Elective) Essay Chapter 4 – Tribal Verse

by G.N. Devy

“Tribal Verse” by G.N. Devy is an essay that examines the oral storytelling traditions of India’s tribal communities. It highlights their unique way of seeing the world and expressing themselves artistically. The essay stresses the importance of these oral traditions, which are passed down through generations. It also raises concerns about the risk of losing these traditions due to print culture, urbanization, and commercialization.

Related:

- Tribal Verse Question Answers

Tribal Verse Summary

The essay, “Tribal Verse” by G.N. Devy, introduces us to the rich oral literary traditions of India’s tribal or Adivasi communities. It argues that these ancient verbal traditions are a vital part of India’s literary heritage, even though many have been lost because they were never written down. Modern forces like city development, print culture, and business have pushed these communities, their languages, and their unique literary forms to the side. The author stresses the urgent need to collect and preserve these oral literatures before more of this “invaluable part of our history” disappears.

The essay argues for a new way to understand literature, one that doesn’t ignore oral expressions as just casual talk. It introduces three specific tribal songs as examples: a Munda song for childbirth, a Kondh song for death, and an Adi chanting for health. These songs show the vast diversity among tribal groups and how their specific locations and histories influence their unique traditions. It also points out that many tribal groups are bilingual and that some, like the Santhal and Munda, have played significant roles in social and political movements, such as the Jharkhand Movement.

The songs selected offer a glimpse into the “rich repository of folk songs” that express the tribal vision of life. This vision is deeply connected to nature, with a belief in the interdependence between humans and the natural world. For tribals, nature is alive and responsive, demanding respect for coexistence. The essay acknowledges that translating these songs into English inevitably causes some loss of their original flavor but emphasizes that translation is the only way for these works to be accessed and preserved by a wider audience.

The essay then moves to describe tribal communities globally as cohesive and organically unified groups. They generally have little interest in gathering wealth and view nature, humans, and God as intimately connected. Their understanding of truth often comes from intuition rather than reason, and they see space as sacred, with a personal sense of time. This makes their way of imagining the world very different from modern society, which often separates the creator from God and prefers self-conscious, logical thought.

Tribal imagination is described as “dreamlike and hallucinatory,” naturally allowing different parts of existence and time to merge. In their stories, animals speak, mountains swim, and stars grow like plants, showing that spatial order and time limits don’t apply. While they do have rules for their creations, these rules allow for a natural connection between emotion and the story’s theme.

The author suggests that tribal artists rely more on their “racial and sensory memory” than on a cultivated imagination. They seem to have realized that controlling physical land was not their destiny, so they focused on dominating time, evidenced by their rituals of speaking with dead ancestors. This has led to an “amazingly sharp memory” for classifying knowledge.

The essay laments that many Indian oral languages are not considered ‘literature’ simply because they are not written down. It mentions nomadic communities held together by oral epics and expresses shame at the neglect of this vast wealth. The author states that he can no longer think of literature only as written text and urges a change in this established notion to prevent the decline of Indian oral traditions. He reminds us that written scripts and printing are relatively new inventions compared to the ancient human ability to create speech that lasts through time.

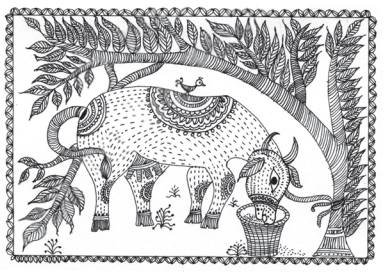

The essay also explains that tribal arts have a distinct way of creating space and images, which is “hallucinatory.” The lines between art and everyday life are blurred, with tribal paintings merging with living spaces and narratives starting from trivial events. There’s no strict sequence, and episodes often appear chaotic like dreams, with mixtures of old and new imagery. Despite this apparent freedom, tribal arts follow very strict conventions, adhering to past traditions while playfully making small changes.

Playfulness is described as the “soul of tribal arts.” Even though tribal art is deeply linked to sacred rituals, it rarely takes a serious tone. Artists often don’t see themselves as the sole “Creator,” and humor is common. This unique blend of sacred and ordinary might be because tribal art is not created for sale; artists receive patronage, but without competition, leading to relaxed, non-tense creations. The essay challenges the misconception that orally transmitted arts are static; it clarifies that they are dynamic, involving performance and audience reception, allowing for experimentation.

Finally, the essay notes that Indian tribal communities are mostly bilingual, giving them a natural ability to take in outside influences. Their oral stories and songs use bilingualism in complex ways. The author also critically observes that classifying works by contemporary Indian writers (who come from ancient multilingual traditions) as “new literature” by Western academics was “comical.” He emphasizes that Adivasi literature is not a “new movement” but has simply been unrecognized. He stresses the need to see tribal imaginative expression as literature, not just folklore, and tribal speech as a language, not just a dialect. He reminds us that written literature itself contains layers of orality and that speech transcends time.

The three selected songs provide specific examples of these themes:

A Munda Song: Song of Birth and Death: This song, translated from Mundari, celebrates the birth of a son or daughter, deeply connecting it to nature (sun, moon, cowshed). It reveals a unique Munda belief where the birth of a daughter is associated with a full cowshed (a sign of prosperity and blessing), while a son’s birth is linked to its depletion. This highlights the Munda society’s dominant role for women and their perception of daughters as more precious assets.

A Kondh Song: This song is sung at a death, offering a baby fowl to the spirit of the deceased. It reflects the Kondh belief that dead spirits are reluctant to leave their homes and can cause trouble if not appeased. The song is a plea for the spirit to accept the offering and not inflict pain, showing a pragmatic and respectful approach to the spirit world, emphasizing the living’s desire to prosper and continue making offerings.

Adi Song for the Recovery of Lost Health: This is a mantra chanted in Miri Agom (a ritualistic language) to bring back the spirit of good health to a sick person. The Adi believe illness occurs when the health spirit abandons the body. The maternal uncle performs the ritual, using objects like an amulet (Emul) and a Ridin creeper, and an offering like a cock, to persuade the spirit to return to its “sweet home” (the body), illustrating their spiritual understanding of health and their connection to nature for healing.

Summary of the Lesson Tribal Verse in Hindi

निबंध, G.N. द्वारा “जनजातीय श्लोक”। देवी, हमें भारत के आदिवासी या आदिवासी समुदायों की समृद्ध मौखिक साहित्यिक परंपराओं से परिचित कराती हैं। यह तर्क देता है कि ये प्राचीन मौखिक परंपराएं भारत की साहित्यिक विरासत का एक महत्वपूर्ण हिस्सा हैं, भले ही उनमें से कई खो गए हैं क्योंकि उन्हें कभी लिखा नहीं गया था। शहरी विकास, मुद्रण संस्कृति और व्यवसाय जैसी आधुनिक शक्तियों ने इन समुदायों, उनकी भाषाओं और उनके अनूठे साहित्यिक रूपों को किनारे कर दिया है। लेखक “हमारे इतिहास के इस अमूल्य हिस्से” के गायब होने से पहले इन मौखिक साहित्य को एकत्र करने और संरक्षित करने की तत्काल आवश्यकता पर जोर देते हैं।

निबंध साहित्य को समझने के एक नए तरीके के लिए तर्क देता है, जो मौखिक अभिव्यक्तियों को केवल अनौपचारिक बातचीत के रूप में अनदेखा नहीं करता है। इसमें उदाहरण के रूप में तीन विशिष्ट आदिवासी गीतों का परिचय दिया गया हैः बच्चे के जन्म के लिए एक मुंडा गीत, मृत्यु के लिए एक कोंध गीत और स्वास्थ्य के लिए एक आदि जप। ये गीत आदिवासी समूहों के बीच विशाल विविधता को दर्शाते हैं और कैसे उनके विशिष्ट स्थान और इतिहास उनकी अनूठी परंपराओं को प्रभावित करते हैं। यह भी बताता है कि कई आदिवासी समूह द्विभाषी हैं और कुछ, जैसे संथाल और मुंडा, ने झारखंड आंदोलन जैसे सामाजिक और राजनीतिक आंदोलनों में महत्वपूर्ण भूमिका निभाई है।

चयनित गीत “लोक गीतों के समृद्ध भंडार” की एक झलक पेश करते हैं जो आदिवासी “जीवन की दृष्टि” को व्यक्त करते हैं। यह दृष्टि मनुष्यों और प्राकृतिक दुनिया के बीच परस्पर निर्भरता में विश्वास के साथ प्रकृति से गहराई से जुड़ी हुई है। आदिवासियों के लिए, प्रकृति जीवित और उत्तरदायी है, जो सह-अस्तित्व के लिए सम्मान की मांग करती है। पाठ स्वीकार करता है कि इन गीतों का अंग्रेजी में अनुवाद करने से अनिवार्य रूप से उनके मूल स्वाद का कुछ नुकसान होता है, लेकिन इस बात पर जोर दिया जाता है कि अनुवाद ही इन कार्यों को व्यापक दर्शकों द्वारा एक्सेस और संरक्षित करने का एकमात्र तरीका है।

इसके बाद निबंध में वैश्विक स्तर पर जनजातीय समुदायों को “एकजुट और व्यवस्थित रूप से एकीकृत” समूहों के रूप में वर्णित किया गया है। वे आम तौर पर धन इकट्ठा करने में बहुत कम रुचि रखते हैं और प्रकृति, मनुष्यों और भगवान को घनिष्ठ रूप से जुड़े हुए मानते हैं। सत्य की उनकी समझ अक्सर तर्क के बजाय अंतर्ज्ञान से आती है, और वे समय की व्यक्तिगत भावना के साथ स्थान को पवित्र के रूप में देखते हैं। यह दुनिया की कल्पना करने के उनके तरीके को आधुनिक समाज से बहुत अलग बनाता है, जो अक्सर निर्माता को भगवान से अलग करता है और आत्म-जागरूक, तार्किक विचार को पसंद करता है।

जनजातीय कल्पना को “स्वप्निल और मतिभ्रमपूर्ण” के रूप में वर्णित किया गया है, जो स्वाभाविक रूप से अस्तित्व और समय के विभिन्न हिस्सों को विलय करने की अनुमति देता है। उनकी कहानियों में, जानवर बोलते हैं, पहाड़ तैरते हैं, और तारे पौधों की तरह बढ़ते हैं, जो दर्शाता है कि स्थानिक क्रम और समय सीमाएं लागू नहीं होती हैं। हालांकि उनके पास अपनी रचनाओं के लिए नियम हैं, ये नियम भावना और कहानी के विषय के बीच एक स्वाभाविक संबंध की अनुमति देते हैं।

लेखक का सुझाव है कि आदिवासी कलाकार अपनी संवर्धित कल्पना की तुलना में अपनी “नस्लीय और संवेदी स्मृति” पर अधिक भरोसा करते हैं। ऐसा लगता है कि उन्होंने महसूस किया है कि भौतिक भूमि को नियंत्रित करना उनकी नियति नहीं थी, इसलिए उन्होंने समय पर हावी होने पर ध्यान केंद्रित किया, जिसका प्रमाण मृत पूर्वजों के साथ बात करने के उनके अनुष्ठानों से मिलता है। इसने ज्ञान को वर्गीकृत करने के लिए एक “आश्चर्यजनक रूप से तेज स्मृति” को जन्म दिया है।

निबंध में कहा गया है कि कई भारतीय मौखिक भाषाओं को केवल इसलिए ‘साहित्य’ नहीं माना जाता है क्योंकि वे लिखी नहीं जाती हैं। इसमें मौखिक महाकाव्यों द्वारा एक साथ रखे गए खानाबदोश समुदायों का उल्लेख किया गया है और इस विशाल धन की उपेक्षा पर शर्म व्यक्त की गई है। लेखक का कहना है कि वह अब साहित्य को केवल लिखित पाठ के रूप में नहीं सोच सकते हैं और भारतीय मौखिक परंपराओं के पतन को रोकने के लिए इस “स्थापित धारणा” में बदलाव का आग्रह करते हैं। वह हमें याद दिलाते हैं कि लिखित लिपियाँ और मुद्रण समय के साथ चलने वाले भाषण बनाने की प्राचीन मानव क्षमता की तुलना में अपेक्षाकृत नए आविष्कार हैं।

निबंध में यह भी बताया गया है कि जनजातीय कलाओं में स्थान और छवियों को बनाने का एक अलग तरीका है, जो “मतिभ्रमपूर्ण” है। कला और रोजमर्रा के जीवन के बीच की रेखाएँ धुंधली हो जाती हैं, जिसमें आदिवासी चित्रों का रहने की जगहों के साथ विलय हो जाता है और छोटी-मोटी घटनाओं से कथाएँ शुरू होती हैं। कोई सख्त अनुक्रम नहीं है, और एपिसोड अक्सर पुरानी और नई कल्पनाओं के मिश्रण के साथ सपनों की तरह “अराजक” दिखाई देते हैं। इस स्पष्ट स्वतंत्रता के बावजूद, आदिवासी कलाएँ बहुत सख्त परंपराओं का पालन करती हैं, अतीत की परंपराओं का पालन करते हुए छोटे-छोटे बदलाव करती हैं।

चंचलता को “आदिवासी कलाओं की आत्मा” के रूप में वर्णित किया गया है। भले ही आदिवासी कला पवित्र अनुष्ठानों से गहराई से जुड़ी हुई है, लेकिन यह शायद ही कभी गंभीर रूप लेती है। कलाकार अक्सर खुद को एकमात्र “निर्माता” के रूप में नहीं देखते हैं, और हास्य आम है। पवित्र और साधारण का यह अनूठा मिश्रण इसलिए हो सकता है क्योंकि आदिवासी कला को बिक्री के लिए नहीं बनाया जाता है; कलाकारों को संरक्षण मिलता है, लेकिन प्रतिस्पर्धा के बिना, आराम से, गैर-तनावपूर्ण रचनाओं की ओर ले जाता है। निबंध इस गलत धारणा को चुनौती देता है कि मौखिक रूप से प्रसारित कलाएं स्थिर हैं; यह स्पष्ट करता है कि वे गतिशील हैं, जिसमें प्रदर्शन और दर्शकों का स्वागत शामिल है, जिससे प्रयोग करने की अनुमति मिलती है।

अंत में, निबंध में कहा गया है कि भारतीय आदिवासी समुदाय ज्यादातर द्विभाषी हैं, जो उन्हें बाहरी प्रभावों को लेने की स्वाभाविक क्षमता देते हैं। उनकी मौखिक कहानियों और गीतों में जटिल तरीकों से द्विभाषिकता का उपयोग किया जाता है। लेखक का यह भी मानना है कि समकालीन भारतीय लेखकों (जो प्राचीन बहुभाषी परंपराओं से आते हैं) की रचनाओं को पश्चिमी शिक्षाविदों द्वारा “नए साहित्य” के रूप में वर्गीकृत करना “हास्यपूर्ण” था। वह इस बात पर जोर देते हैं कि आदिवासी साहित्य एक “नया आंदोलन” नहीं है, बल्कि इसे मान्यता नहीं दी गई है। उन्होंने जनजातीय कल्पनाशील अभिव्यक्ति को साहित्य के रूप में देखने की आवश्यकता पर जोर दिया, न कि केवल लोककथाओं और जनजातीय भाषण को एक भाषा के रूप में, न कि केवल एक बोली के रूप में। वे हमें याद दिलाते हैं कि लिखित साहित्य में ही मौखिकता की परतें होती हैं और भाषण समय से परे है।

तीन चयनित गीत इन विषयों के विशिष्ट उदाहरण प्रदान करते हैंः

एक मुंडा गीतः जन्म और मृत्यु का गीतः मुंडारी से अनुवादित यह गीत एक बेटे या बेटी के जन्म का जश्न मनाता है, जो इसे प्रकृति (सूर्य, चंद्रमा, गौशाला) से गहराई से जोड़ता है। यह एक अद्वितीय मुंडा विश्वास को प्रकट करता है जहां एक बेटी का जन्म एक पूर्ण गौशाला (समृद्धि और आशीर्वाद का संकेत) से जुड़ा होता है, जबकि एक बेटे का जन्म इसकी कमी से जुड़ा होता है। यह महिलाओं के लिए मुंडा समाज की प्रमुख भूमिका और बेटियों को अधिक मूल्यवान संपत्ति के रूप में उनकी धारणा को उजागर करता है।

एक कोंध गीतः यह गीत मृत्यु के समय गाया जाता है, जिसमें मृतक की आत्मा को एक शिशु पक्षी चढ़ाया जाता है। यह कोंध विश्वास को दर्शाता है कि मृत आत्माएं अपने घरों को छोड़ने के लिए अनिच्छुक होती हैं और शांत नहीं होने पर परेशानी पैदा कर सकती हैं। यह गीत आत्मा के लिए एक निवेदन है कि वह भेंट को स्वीकार करे और दर्द न दे, आत्मिक दुनिया के प्रति एक व्यावहारिक और सम्मानजनक दृष्टिकोण दिखाता है, जो जीवित लोगों की समृद्धि और प्रसाद देना जारी रखने की इच्छा पर जोर देता है।

खोए हुए स्वास्थ्य की वसूली के लिए आदि गीतः यह एक बीमार व्यक्ति को अच्छे स्वास्थ्य की भावना वापस लाने के लिए मीरी अगोम (एक अनुष्ठानिक भाषा) में जप किया जाने वाला एक मंत्र है। आदि का मानना है कि बीमारी तब होती है जब स्वास्थ्य आत्मा शरीर को छोड़ देती है। मामा अनुष्ठान करते हैं, एक ताबीज (एमुल) और एक रिडिन लता जैसी वस्तुओं का उपयोग करते हुए, और एक मुर्गा की तरह एक भेंट, आत्मा को अपने “मीठे घर” (शरीर) में लौटने के लिए मनाने के लिए स्वास्थ्य की उनकी आध्यात्मिक समझ और उपचार के लिए प्रकृति के साथ उनके संबंध को दर्शाते हैं।

Theme of the Lesson Tribal Verse

The Importance and Neglect of Oral Literature

The essay highlights that India’s literary heritage has deep roots in the oral traditions of tribal communities. These verses, often songs or chants, express a close connection between nature and tribal life. They’ve been passed down through generations, but a large number are now lost because they weren’t written. The author emphasizes that urban development, print culture, and commerce have not only pushed these communities aside but also their unique languages and literary forms. This theme calls attention to the danger of losing an invaluable part of history if more effort isn’t made to preserve these oral traditions.

Redefining Literature and Challenging Western Bias

Devy argues for a broader definition of literature that includes oral tribal expressions, challenging the traditional view that only written texts are considered literature. He points out that many Indian languages are only spoken, leading to their rich compositions being dismissed as mere folklore or dialects by mainstream literary critics, especially those influenced by Western academic classifications. This theme advocates for recognizing tribal speech and imaginative expression as legitimate literature, reminding us that written scripts and printing are relatively new compared to humanity’s ancient ability to create enduring speech.

The Distinctive Tribal Worldview and Imagination

A key theme is the unique way tribal communities perceive the world, which radically differs from modern society. They live in cohesive groups with little interest in accumulating wealth, believing that nature, humans, and God are intimately linked. They rely more on intuition than reason, see space as sacred, and have a personal sense of time. Their imagination is described as dreamlike and hallucinatory, allowing for a fluid merging of different realities, where animals speak and mountains swim. This challenges the rigid, self-conscious, and often secular worldview of modern societies.

Memory, Convention, and Playfulness in Tribal Arts

The essay explores how tribal arts are shaped by “racial and sensory memory” and strict conventions. Tribal artists adhere to past traditions while playfully “subverting” or subtly changing them, showing that their art is dynamic, not static. Playfulness is presented as the “soul” of tribal arts, which, despite being linked to sacred rituals, rarely take a serious or pretentious tone. This theme emphasizes that tribal art is not created for sale, leading to a relaxed, non-competitive artistic process where humor and everyday life blend with the sacred.

Tribal Verse Explanation

Passage: The roots of India’s literary traditions can be traced to the rich oral literatures of the tribes/adivasis. Usually in the form of songs or chanting, these verses are expressions of the close contact between the world of nature and the world of tribal existence. They have been orally transmitted from generation to generation and have survived for several ages. However, a large number of these are already lost due to the very fact of their orality. The forces of urbanisation, print culture and commerce have resulted in not just the marginalisation of these communities but also of their languages and literary cultures. Though some attempts have been made for the collection and conservation of tribal languages and their literatures, without more concerted efforts at an acelerated pace, we are in danger of losing an invaluable part of our history and rich literary heritage.

Word meanings

Roots: The origins or beginnings.

Traced: Followed back to its source or origin.

Oral literatures: Stories, poems, or songs that are passed down by speaking, rather than writing.

Adivasis: Indigenous tribal communities of India.

Chanting: Repeating words or sounds in a rhythmic, often melodic, way.

Verses: Lines of poetry or parts of a song.

Orally transmitted: Passed down by word of mouth; spoken from one person to another.

Orality: The characteristic of being spoken rather than written.

Urbanisation: The process by which cities grow and more people live in urban areas.

Print culture: The widespread use and influence of printed materials (like books, newspapers).

Commerce: Business activity; trade.

Marginalisation: The process of pushing a group or community to the edges of society, making them less important or powerful.

Literary cultures: The ways of creating, sharing, and appreciating stories, poems, and other forms of literature.

Concerted efforts: Efforts that are planned and carried out together by many people.

Accelerated pace: A faster rate or speed.

Literary heritage: The tradition of stories, poems, and other written or spoken works passed down from previous generations.

Explanation of the above passage—India’s literary past started from the rich spoken stories and songs of tribes/Adivasis. Usually as songs or chants, these verses show the close connection between nature and tribal life. They have been passed down by word of mouth from one generation to the next and have lived for many ages. But, many of these are already gone because they were only spoken. The power of city growth, printed books, and business has caused not just the pushing aside of these groups but also of their languages and ways of writing. Even though some efforts have been made to collect and save tribal languages and their literatures, without more focused efforts at a faster speed, one risks losing a priceless part of their history and rich literary past.

Passage: This is followed by two songs—one sung on the occasion of childbirth by the Munda tribals and the other on the occasion of death by the Kondh tribals. The third verse is a chanting in the ritualistic religious language of the Adi tribe, not the same as their language of conversation. Even though this is merely a small representation of a treasure of tribal/adivasi songs, it indicates the immense diversity that exists amongst tribal groups. Inevitably influenced by their very specific historical, cultural and geographical locations, tribal societies continue to retain and reproduce their distinctive traditions which usually find expression through their different languages. However, it is equally true that though possessing their very specific languages, most tribal societies such as Munda, Kondh, Adi and Bondo are bilingual. Moreover, while tribal groups like the Santhal become important subjects in dominant literary streams such as Bangla literature, there is a fairly well developed Santhali literature too. Besides this, tribes like Santhal and Munda have also played a prominent role in the sociopolitical movements of their regions. [Birsa Munda (1874–1901) spent his whole life fighting against colonialism and the exploitation of labourers]. The Santhals have emerged as a prominent group at the regional and state levels through their participation in the Jharkhand Movement.

Word meanings

Occasion: A particular time or event when something happens.

Chanting: Saying or singing words in a repetitive, rhythmic way, often for a ritual or prayer.

Ritualistic: Relating to or done as part of a ritual (a fixed series of actions performed in a ceremony, especially a religious one).

Religious: Connected to religion or belief in a god or gods.

Representation: A display or example of something.

Immense: Extremely large or great.

Diversity: The quality or state of being different or varied.

Inevitably: As is certain to happen; unavoidably.

Historical: Relating to history or past events.

Cultural: Relating to the customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or group.

Geographical: Relating to the physical features of the Earth or an area.

Reproduce: To produce again; to make a copy or something similar.

Distinctive: Clearly different from others of the same kind.

Traditions: Customs or beliefs passed down from generation to generation.

Possessing: Having or owning something.

Bilingual: Able to speak two languages fluently.

Literary streams: Major movements or categories within literature.

Sociopolitical: Relating to both social and political factors.

Movements: Groups of people working together to advance shared political, social, or artistic ideas.

Colonialism: The policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

Exploitation: The action or fact of treating someone unfairly in order to benefit from their work.

Emergence: The process of coming into being, or of becoming known.

Jharkhand Movement: A political movement for the creation of a separate state of Jharkhand for tribal people in India.

Explanation of the above passage—One song is sung by the Munda tribals when a child is born. The other song is sung by the Kondh tribals when someone dies. The third verse is a chanting used in the religious rituals of the Adi tribe; this language is different from their everyday talking language. Even though these songs are only a small example of the many valuable tribal/Adivasi songs, this small collection shows how much variety there is among different tribal groups. Tribal societies are naturally shaped by their unique past, culture, and where they live. They keep and pass on their special traditions, which they usually express through their different languages. However, it is also true that most tribal groups like Munda, Kondh, Adi, and Bondo, even though they have their own specific languages, can speak two languages (are bilingual). Also, while tribal groups like the Santhals are often important topics in major written literatures like Bangla literature, there is also a good, developed literature in the Santhali language itself. In addition to this, tribes like Santhals and Mundas have also played a big part in social and political movements in their areas. For example, Birsa Munda (who lived from 1874 to 1901) spent his entire life fighting against rule by other countries and against workers being unfairly used. The Santhals have become a strong group at the regional and state levels because of their involvement in the Jharkhand Movement.

Passage: The three selected songs give us a small glimpse into the rich repository of folk songs that is an expression of the tribal vision of life. Their close connection with nature is evident from their belief in the interdependence between human beings and nature. Nature for them is living and responsive to human existence and human actions, demanding respect essential for any kind of coexistence.

The songs exist originally in the native languages of the tribals and are sung or chanted. The effort to bring them to students in English naturally involves some loss of the original flavour and spirit but that is a problem of all translation and constant attempts need to be made to minimise this loss. But for some conscious effort being made to first preserve these songs, these pieces of literature would have been lost to us completely. However limitedly, it is only through translation that we are able to even access these works.

Word meanings

Glimpse: A quick, brief look.

Repository: A place where a large amount of something is stored; a collection.

Expression: A way of showing or communicating something.

Tribal vision of life: The unique way a tribal community understands and sees the world, their beliefs and values.

Interdependence: The state of depending on each other; mutual reliance.

Coexistence: The state of living or existing together at the same time or in the same place.

Native languages: The original or indigenous languages of a particular place or group of people.

Spirit: the essential character/mood of something.

Conscious effort: Deliberate and intentional work or attempt.

Preserve: To keep something in its original state or in good condition; to prevent it from decaying or being lost.

Limitedly: In a restricted or small way; to a small extent.

Access: The ability, right, or opportunity to approach or use something.

Explanation of the above passage— The three songs chosen give a small peek into the rich collection of folk songs. This collection shows the tribal way of looking at life. Their strong bond with nature is clear because they believe humans and nature depend on each other. For them, nature is alive and reacts to human life and actions, needing respect for everyone to live together. The songs are originally in the native languages of the tribal people and are sung or chanted. The act of bringing them to students in English naturally causes some loss of their original feeling and essence. But that is a common problem with all translation, and continuous efforts must be made to make this loss as small as possible. If some deliberate effort were not made to first save these songs, these literary pieces would have been completely lost to us. Even though it’s limited, only through translation the readers even can get to these works.

‘INTRODUCTION’ TO PAINTED WORDS

Passage: …Most tribal communities in India are culturally similar to tribal communities elsewhere in the world. They live in groups that are cohesive and organically unified. They show very little interest in accumulating wealth or in using labour as a device to gather interest and capital. They accept a world-view in which nature, human beings and God are intimately linked and they believe in the human ability to spell and interpret truth. They live more by intution than reason, they consider the space around them more sacred than secular, and their sense of time is personal rather than objective. The world of the tribal imagination, therefore, is radically different from that of modern Indian society.

Word meanings

Culturally similar: Having similar ways of life, customs, beliefs, and traditions.

Cohesive: Sticking together; forming a united and close group.

Organically unified: Naturally growing together to form a single, complete, and harmonious whole, like parts of a living body.

Accumulating wealth: Gathering or collecting a lot of money, possessions, or riches.

Labour as a device to gather interest and capital: Using work not just for immediate needs, but to earn more money from money (interest) or to build up large sums of money for investment (capital).

World-view: A particular philosophy of life or conception of the world; how someone sees and understands the world.

Intimately linked: Very closely connected or related.

Spell and interpret truth: To understand, explain, and make sense of truth.

Intuition: The ability to understand something immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning. It’s a gut feeling or instinct.

Secular: Not connected with religious or spiritual matters; worldly rather than spiritual.

Personal (sense of time): Time experienced and felt individually, often based on natural rhythms or events, rather than measured by clocks or calendars.

Objective (sense of time): Time measured independently of individual feelings or perceptions, like clock time (e.g., minutes, hours, years).

Radically different: Completely or fundamentally different.

Explanation of the above passage—The author states that most tribal groups in India are culturally alike to tribal groups in other parts of the world. They live in communities that are tightly connected and naturally joined together. They show very little desire in collecting riches or in using work as a way to gather profit and money. They accept a way of seeing the world in which nature, people, and God are closely connected, and they believe in the human power to understand and explain truth. They live more by inner feeling than by logical thought. They consider the area around them more holy than ordinary, and their idea of time is personal rather than based on exact measurements. The world that tribal imagination creates, therefore, is completely different from the world of modern Indian society.

Passage: Once a society accepts a secular mode of creativity within which the creator replaces God, imaginative transactions assume a self-conscious form. The tribal imagination, on the other hand, is still, to a large extent, dreamlike and hallucinatory. It admits fusion between various planes of existence and levels of time in a natural way. In tribal stories, oceans fly in the sky as birds, mountains swim in the water as fish, animals speak as humans and stars grow like plants. Spatial order and temporal sequence do not restrict the narrative. This is not to say that tribal creations have no conventions or rules but simply that they admit the principle of association between emotion and the narrative motif. Thus stars, seas, mountains, trees, men and animals, can be angry, sad or happy.

Word meanings

Secular: Not religious; not connected with spiritual or religious matters.

Mode: A way or manner in which something is done or experienced.

Creativity: The ability to make new things or think of new ideas.

Creator: A person who makes or invents something.

Imaginative transactions: The exchange or expression of ideas that come from imagination.

Self-conscious: Aware of oneself as an individual or of one’s own actions, thoughts, and appearance. The creative act is highly aware of itself and its maker.

Tribal: Relating to a tribe (a group of people, often with a common language and culture, especially in a traditional society).

Dreamlike: Resembling a dream; vague or unreal.

Hallucinatory: Producing hallucinations (experiences that seem real but are not), or like a hallucination; vivid or fantastical.

Fusion: The process or result of joining two or more things together to form a single entity.

Various planes of existence: Different levels or realities of being (e.g., physical, spiritual, dream).

Levels of time: Different points or dimensions of time (e.g., past, present, future) that can merge.

Natural way: In an unforced or instinctive manner.

Spatial order: The arrangement of things in space; how things are organized geographically or visually.

Temporal sequence: The order of events in time; chronological order.

Conventions: Established rules or practices.

Dialects: Forms of a language spoken in a specific region or by a specific group, often considered less standard.

Principle of association: A basic rule that allows ideas, emotions, or things to be linked together.

Narrative motif: A repeated theme, idea, or element in a story.

Explanation of the above passage— Once a society agrees to a non-religious way of creating things, where the person creating becomes like God, then imaginative exchanges become very aware of themselves. The tribal imagination, however, is still mostly like a dream and full of visions. It allows different levels of reality and different times to naturally mix together. In tribal stories, oceans fly in the sky like birds, mountains swim in the water like fish, animals talk like humans, and stars grow like plants. The order of space and the order of time do not limit the story. This does not mean that tribal creations have no rules; it just means they allow feelings to be directly linked with the main idea of the story. So, stars, seas, mountains, trees, people, and animals can show anger, sadness, or happiness.

Passage: It might be said that tribal artists work more on the basis of their racial and sensory memory than on the basis of a cultivated imagination. In order to understand this distinction, we must understand the difference between imagination and memory. In the animate world, consciousness meets two immediate material realities: space and time. We put meaning into space by perceiving it in terms of images. The image making faculty is a genetic gift to the human mind—this power of imagination helps us understand the space that envelops us. In the case of time, we make connections with the help of memory; one remembers being the same person as one was yesterday.

Word meanings

Racial memory: This refers to a collective memory or shared experiences believed to be inherited or deeply ingrained within a particular racial or ethnic group, passed down through generations, rather than learned individually.

Sensory memory: Memory related to the five senses (sight, sound, smell, touch, taste), recalling experiences based on what was physically felt or perceived.

Cultivated imagination: Imagination that has been developed, trained, or refined through education, learning, or deliberate practice, rather than being purely innate or spontaneous.

Animate world: The world of living things (plants, animals, humans), as opposed to inanimate (non-living) objects.

Consciousness: The state of being aware of one’s own existence and surroundings; awareness.

Material realities: Physical things that actually exist, as opposed to abstract ideas or concepts.

Space: The continuous area or expanse that is free, available, or occupied. The physical environment around us.

Time: The indefinite continued progress of existence and events in the past, present, and future regarded as a whole.

Perceiving: Becoming aware or conscious of something; understanding something in a particular way.

Images: Mental pictures or representations; visual forms.

Image making faculty: The mental ability or power to create or form images in the mind.

Genetic gift: A natural ability or characteristic that is inherited from one’s parents or ancestors, part of one’s DNA.

Envelops: Surrounds or covers completely

Explanation of the above passage— It might be said that tribal artists work more on the basis of their racial and sense-based memory rather than on the basis of a developed imagination. To understand this difference, one must understand the difference between creativity and imagination. In the living world, awareness meets two direct physical realities: space and time. People put meaning into space by seeing it as pictures. The picture-making ability is a natural gift to the human mind—this power of creativity helps people understand the space that surrounds them. For time, people make links with the help of memory; one remembers being the same person as one was the day before.

Passage: The tribal mind has a more acute sense of time than sense of space. Somewhere along the history of human civilization, tribal communities seem to have realised that domination over territorial space was not their lot. Thus, they seem to have turned almost obsessively to gaining domination over time. This urge is substantiated in their ritual of conversing with their dead ancestors: year after year, tribals in many parts of India worship terracotta, or carved-wood objects, representing their ancestors, aspiring to enter a trance in which they can converse with the dead. Over the centuries, an amazingly sharp memory has helped tribals classify material and natural objects into a highly complex system of knowledge. The importance of memory in tribal systems of knowledge has not yet been sufficiently recognised but the aesthetic proportions of the houses that tribals build, the objects they make and the rituals they perform fascinate the curious onlooker. It can be hard to understand how, without any institutional training or tutoring, tribals are able to dance, sing, craft, build and speak so well …

Word meanings

Acute: Very strong, keen, or sharp.

Domination: Control or power over something.

Territorial space: Physical areas of land or regions.

Obsessively: In a way that shows a persistent and unwanted preoccupation with something.

Urge: A strong desire or impulse.

Substantiated: Supported with evidence or proof; confirmed.

Ritual: A religious or solemn ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order.

Terracotta: A type of reddish-brown clay, often used for pottery and building.

Aspiring: Directing one’s hopes or ambitions toward achieving something.

Trance: A half-conscious state, resembling sleep, in which a person appears detached from their surroundings.

Amazingly: In an astonishing or surprising manner.

Classify: To arrange (a group of people or things) in classes or categories according to shared qualities or characteristics.

Aesthetic proportions: The pleasing or beautiful relationships between the parts of something in terms of size, quantity, or degree.

Fascinate: To attract the strong attention and interest of (someone).

Curious onlooker: A person who watches something with interest and a desire to know more.

Institutional training: Formal education or instruction received in an organized school, college, or other institution.

Tutoring: Instruction or teaching given by a private tutor or instructor.

Explanation of the above passage— The tribal mind possesses a sharper feeling of time compared to a feeling of space. At some point in human history, tribal groups appear to have understood that control over physical land was not their destiny. Therefore, they seem to have focused almost completely on gaining control over time. This strong desire is supported by their tradition of talking with their ancestors who have passed away: every single year, tribal people in many areas of India worship clay or carved-wood figures, which stand for their ancestors. They hope to enter a dream-like state where they can talk to the dead. Over many hundreds of years, an incredibly good memory has helped tribal people to organize everyday and natural things into a very complicated way of knowing. The importance of memory in tribal ways of knowledge has not yet been properly understood, but the beautiful designs of the houses tribal people build, the items they create, and the ceremonies they perform truly interest anyone who watches. It can be difficult to grasp how, without any formal schooling or teaching, tribal people are able to dance, sing, make crafts, build, and communicate so effectively.

Passage: A vast number of Indian languages have yet remained only spoken, with the result that literary compositions in these languages are not considered ‘literature’. They are a feast for the folklorist, anthropologist and linguist but, to a literary critic, they generally mean nothing. Similarly, several nomadic Indian communities are broken up and spread over long distances but survive as communities because they are bound by their oral epics. The wealth and variety of these works is so enormous that one discovers their neglect with a sense of pure shame. Some of the songs and stories I heard from itinerant street singers in my childhood are no longer available anywhere. For some years now I have been collecting songs and stories that circulate in India’s tribal languages, and I am continually overwhelmed by their number and their profound influence on the tribal communities.

Word meanings

Vast: Very large in extent or quantity.

Literary compositions: Creative written or spoken works, such as poems, stories, or plays.

Feast: Something that provides great pleasure or enjoyment, often in abundance.

Folklorist: A person who studies folklore (the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through generations by word of mouth).

Anthropologist: A person who studies human societies, cultures, and their development.

Linguist: A person who studies languages.

Literary critic: A person who analyzes and evaluates literary works.

Nomadic: Living a life of wandering; not settled in one place.

Communities: Groups of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common.

Bound by: Held together or united by.

Oral epics: Long narrative poems or stories that are traditionally passed down by word of mouth from one generation to another.

Wealth: A large amount of valuable possessions or resources; here, it means a rich abundance of literary works.

Pure shame: Deep and strong feeling of shame.

Itinerant: Traveling from place to place, especially to perform work.

Circulate: To move around freely.

Overwhelmed: deeply impressed or greatly affected.

Profound: Very great or intense; having deep meaning or importance.

Explanation of the above passage—A very large number of Indian languages still exist only as spoken languages. Because of this, creative writings and works in these languages are not thought of as ‘literature’. These works are a great pleasure for people who study folklore, human societies (anthropologists), and languages (linguists). However, for a person who judges literature (literary critic), these works usually mean nothing. In a similar way, many traveling Indian communities are separated and spread across far distances. But they continue to exist as communities because their long oral stories (epics) tie them together. The huge amount and many different kinds of these works are so great that one finds their lack of attention with a feeling of deep shame. Some of the songs and stories the author heard from traveling street singers when he was a child cannot be found anywhere now. For some years until now, the author has been gathering songs and stories that are common in India’s tribal languages. And the author is constantly amazed by how many there are and how deeply they affect the tribal communities.

Passage: The result is that I, for one, can no longer think of literature as something written. Of course I do not dispute the claim of written compositions and texts to the status of literature; but surely it is time we realise that unless we modify the established notion of literature as something written, we will silently witness the decline of various Indian oral traditions. That literature is a lot more than writing is a reminder necessary for our times.

Word meanings

Dispute: To argue against something; to question the truth or validity of something.

Claim: A statement that something is true, often without direct proof; or a right to something.

Status: The position or standing of something in relation to others; its rank or importance.

Modify: To change something slightly, especially to make it more suitable for a particular purpose.

Established notion: A widely accepted or commonly held idea or belief that has been in place for a long time.

Silently witness: To see something happen without doing anything to stop it or without making any protest.

Explanation of the above passage— The result is that the author, for himself, can no longer think of literature as only something written. Of course, he does not argue against the idea that written compositions and texts deserve the title of literature. But he believes strongly that it is time for people to understand that unless they change the accepted idea of literature as only written material, they will quietly watch the disappearance of many different Indian oral traditions. He states that the idea that literature is much more than just writing is a necessary reminder for our current times.

Passage: One of the main characteristics of tribal arts is their distinct manner of constructing space and imagery, which might be described as ‘hallucinatory’. In both oral and visual forms of representation, tribal artists seem to interpret verbal or pictorial space as demarcated by an extremely flexible ‘frame’. The boundaries between art and non-art become almost invisible. A tribal epic can begin its narration from a trivial everyday event; tribal paintings merge with living space as if the two were one and the same. And within the narrative itself, or within the painted imagery, there is no deliberate attempt to follow a sequence. The episodes retold and the images created take on the apparently chaotic shapes of dreams. In a tribal Ramayan, an episode from the Mahabharat makes a sudden and surprising appearance; tribal paintings contain a curious mixture of traditional and modern imagery. In a way, the syntax of language and the grammar of painting are the same, as if literature were painted words and painting were a song of images.

Word meanings

Distinct: Easily noticeable or different from others.

Constructing: Building or creating.

Hallucinatory: Like a hallucination; dream-like, visionary, or seeming to see things that aren’t really there.

Representation: The way something is shown or described.

Demarcated: Clearly marked or separated.

Trivial: Of little value or importance.

Merge: To combine or come together to form one thing.

Deliberate: Done on purpose; planned.

Sequence: A particular order in which related things follow each other.

Apparently: As far as one knows or can see; seemingly.

Chaotic: In a state of complete confusion and disorder.

Syntax: The arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language; the rules for forming sentences.

Grammar: The whole system and structure of a language or, here, the rules for how a painting is structured.

Explanation of the above passage— One of the main features of tribal arts is their special way of creating space and pictures, which might be called ‘dream-like’ or ‘visionary’. In both spoken and drawn ways of showing things, tribal artists seem to see spoken or drawn space as being marked by a very flexible ‘border’. The dividing lines between art and everyday things become almost hidden. A tribal long story can start its telling from a small, everyday event; tribal paintings mix with living spaces as if they were the same thing. And inside the story itself, or inside the painted pictures, there is no planned effort to follow an order. The stories were told again and the pictures made look like the messy shapes of dreams. In a tribal Ramayan (a long story), a part from the Mahabharata (another long story) appears suddenly and surprisingly; tribal paintings have a strange mix of old and new pictures. In a way, the rules for language and the rules for painting are the same, as if literature was words painted and painting was a song made of pictures. Tribal art combines painting and literature.

Passage: Yet it is not safe to assume that the tribal arts do not employ any ordering principles. On the contrary, the ordering principles are very strict. The most important among these is convention. Though the casual spectator may not notice, every tribal performance and creation has, at its back, another such performance or creation belonging to a previous occasion. The creativity of the tribal artist lies in adhering to the past while, at the same time, slightly subverting it. The subversions are more playful than ironic.

Word meanings

Employ: To use.

Ordering principles: Rules or methods that bring structure and organization.

On the contrary: The opposite is true; in opposition to what has just been said.

Strict: Very precise, exact, or rigid in following rules.

Convention: A widely accepted way of doing something; tradition or custom.

Casual spectator: Someone who is watching without deep interest or specific knowledge; an ordinary observer.

At its back: Supported by; based on; originating from.

Adhering to: Sticking firmly to; following closely.

Subverting: To undermine the power and authority of (an established system or institution); gently change or challenge the established tradition.

Playful: Full of fun and lightheartedness; not serious.

Ironic: Meaning the opposite of what is expressed; characterized by sarcasm or a mocking tone.

Explanation of the above passage— The author explains that it is incorrect to believe that tribal arts do not use any rules or order. In fact, he states that their ordering rules are very strict. He emphasizes that the most important of these rules is tradition (convention). The author notes that even though someone watching casually might not see it, every tribal show or artwork is based on a similar show or artwork from before. He points out that the tribal artist’s creativity comes from sticking closely to past forms while, at the same time, gently changing them. He clarifies that these small changes are more about playfulness than being sarcastic or mocking.

Passage: Indeed, playfulness is the soul of tribal arts. Though oral and pictorial tribal art creations are intimately related to rituals—the sacred can never be left out—the tribal arts rarely assume a serious or pretentious tone. The artist rarely plays the role of the Creator. Listening to tribal epics can be great fun as even the heroes are not spared the occasional shock of the artist’s humour. One reason for this unique mixture of the sacred and the ordinary may be that tribal works of art are not created specifically for sale. Artists do expect a certain amount of patronage from the community, like artists in any other context; but, since those performing rituals are very often artists themselves, there is no element of competition in the patron-artist relationship. The tribal arts are, therefore, relaxed, never tense… One question invariably asked about the tribal arts is whether they are static—frozen in tradition— or dynamic. A general misconception is that the orally transmitted arts are entirely tradition-bound, with little scope for individual experimentation beyond the small freedom to distort the previously created text. This misconception arises from the habit of seeing art only with reference to the text but the tribal arts involve not just text but performance and audience reception. Experimentation in the tribal arts can be understood only when they are approached as performing arts.

Word meanings

intimately: Very closely; in a close and personal way.

rituals: A series of actions performed in a fixed order, especially as part of a religious or solemn ceremony.

sacred: Holy; connected with God (or gods) or religion; treated as very special and deserving respect.

pretentious: Trying to appear more important, skillful, or knowledgeable than one actually is; showy or trying to impress.

epics: Long narrative poems or stories, typically about heroic deeds and adventures.

spared: Protected from; saved from experiencing something unpleasant.

patronage: The support, encouragement, financial aid, or influence given by a patron (a person or group who supports artists, writers, etc.).

invariably: Always; in every case or on every occasion.

static: Lacking in movement, action, or change; fixed; not moving or changing.

dynamic: Characterized by constant change, activity, or progress.

misconception: A view or opinion that is incorrect because it is based on faulty thinking or understanding.

orally transmitted: Passed down by word of mouth, spoken rather than written.

tradition-bound: Strictly adhering to or limited by customs and practices passed down from generation to generation.

scope: The extent of the area or subject matter that something deals with or to which it is relevant; the opportunity for something.

distort: To pull or twist out of shape; to give a misleading or false account or impression of.

reception: The way in which a person or thing is received or welcomed. Here, how the audience reacts or responds.

Explanation of the above passage— Indeed, playfulness is the soul of tribal arts. Although oral and pictorial tribal art creations are closely linked to rituals— the sacred is always present—the tribal arts almost never sound serious or fake. The artist rarely acts like the Creator (God). Listening to tribal epic stories can be very enjoyable because even the main characters are sometimes surprised by the artist’s humor. One reason for this special mix of holy and ordinary things might be that tribal artworks are not made specifically to be sold. Artists do expect some support from their community, like artists everywhere else; but, since the people performing rituals are often artists themselves, there is no sense of competition in how the community supports the artist. So, tribal artists are relaxed, never tense. One question that is always asked about tribal arts is whether they are fixed and unchanging in tradition, or if they are dynamic (changing and evolving). A common wrong idea is that oral arts, passed down by speaking, are completely bound by tradition, with little room for artists to try new things beyond small changes to old stories. This wrong idea comes from looking at art only as a written text. But tribal arts include not just the words but also the performance and how the audience reacts. New ideas and changes in tribal arts can only be understood when we see them as performing arts.

Passage: Non-tribals usually fail to notice that all of India’s tribal communities are basically bilingual. All bilingual communities have an innate capacity to assimilate outside influences and, in this case, a highly evolved mechanism for responding to the non-tribal world. The tribal oral stories and songs employ bilingualism in such a complex manner that a linguist who is not alert to this complexity is in danger of dismissing the tribal languages altogether as dialects of India’s major tongues…

Word meanings

Non-tribals: People who do not belong to a tribal community.

Bilingual: Able to speak two languages equally well or with similar fluency.

Innate: Existing naturally; inborn, not learned or acquired.

Capacity: The ability or power to do something.

Assimilate: To take in and understand fully; to absorb into the mind or culture. Here, it means to adopt or integrate outside influences.

Outside influences: Ideas, customs, or trends that come from people or cultures different from one’s own.

Evolved mechanism: A system or way of doing things that has developed and become highly effective over time.

Responding: Reacting or behaving in answer to something.

Employ: To make use of.

Complexity: The state of being intricate or complicated.

Linguist: A person who studies language and its structure.

Alert to: Aware of or watchful for something.

Dismissing: Treating something as unworthy of consideration or belief; rejecting.

Dialects: Forms of a language that are peculiar to a specific region or social group, often considered less standard than the main language.

Major tongues: Important or widely spoken languages.

Explanation of the above passage— The author states that people who are not tribal often do not notice that all of India’s tribal groups are mostly able to speak two languages. The author explains that all groups that can speak two languages naturally have a special ability to take in new ideas from outside. In this particular situation (with tribal communities), they have developed a very effective way to react to the world of people who are not tribal. The author points out that the tribal spoken stories and songs use their ability to speak two languages in a very complicated way. Because of this complexity, a linguist (someone who studies language) who is not careful about this duality of languages, might mistakenly consider the tribal languages to be just simpler forms (dialects) of India’s bigger languages.

Passage: The language into which the works have been translated, English, carries massive colonial baggage. When the works of contemporary Indian writers—who inherit a multilingual tradition several thousand years old—were classified as ‘new literature’, Western academics had no idea how comical this classification looked to the literary community in India. Hence it is neccessary to assert that the literature of the adivasis is not a new ‘movement’ or a fresh ‘trend’ in the field of literature; most people have simply been unaware of its existence and that is not the fault of the tribals themselves. What might be new is the present attempt to see imaginative expression in tribal language not as ‘folklore’ but as literature and to hear tribal speech not as a dialect but as a language. This attitude may be somewhat unconventional but only until we recall that scripts themselves are relatively new, and that the printing of literary text goes no further back than a few centuries—in comparison with creative experiments with the human ability to produce speech in such a way that it transcends time. In fact, every written piece of literature contains substantial layers of orality. This is particularly true for poetry and drama but, even in prose fiction, the elements of orality need to be significant if the work is to be effective.

Word meanings

Massive colonial baggage: A huge amount of historical negative influence or problems caused by colonialism (when one country takes control of another, often exploiting it). The historical power imbalance and the way English, as a colonial language, shaped perceptions.

Contemporary: Belonging to or occurring in the present time; modern.

Inherit: To receive something from a predecessor (someone who came before). Indian writers get their literary traditions from past generations.

Comical: Causing laughter, especially because of being strange or absurd; funny.

Classification: The action or process of arranging something into categories or groups.

Assert: To state a fact or belief confidently and forcefully.

Adivasis: Indigenous tribal communities of India.

Movement: A group of people working together to advance their shared political, social, or artistic ideas.

Folklore: The traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through generations by word of mouth. Often used in a way that implies it’s not “high” literature.

Dialect: A particular form of a language that is specific to a region or social group. Often seen as less formal or complete than a “standard” language.

Unconventional: Not based on or conforming to what is generally done or believed; unusual.

Scripts: Systems of writing, like alphabets or characters.

Transcend: To go beyond the limits of; to rise above..

Substantial: Of considerable importance, size, or worth.

Orality: The quality of being spoken or communicated by word of mouth, rather than written.

Prose fiction: Literary works that are not poetry or drama; regular storytelling written in sentences and paragraphs.

Effective: Successful in producing a desired or intended result.

Explanation of the above passage— The author states that the language into which the tribal works have been translated, which is English, carries huge colonial history and influence. He explains that when writings by modern Indian writers, who have a multilingual history thousands of years old, were called ‘new literature,’ Western scholars did not understand how funny this classification seemed to literary people in India. Therefore, he says it is important to state clearly that the literature of the Adivasis (tribal people) is not a new ‘movement’ or a recent ‘trend’ in literature. Instead, he argues that most people have simply been unaware that it existed, and that is not the fault of the tribal people themselves. What might be new, he suggests, is the current effort to view imaginative expression in tribal languages not as ‘folklore’ (simple traditional stories) but as real literature, and to listen to tribal speech not as just a dialect (a regional form of a language) but as a complete language. He acknowledges that this way of thinking might seem a bit unusual, but only until one remembers that written scripts themselves are quite recent. Also, he points out that printing literary texts only started a few hundred years ago, which is very short compared to humans’ long history of creating speech in a way that it lasts beyond time. In fact, he adds, every written piece of literature has significant parts that come from oral traditions. He clarifies that this is especially true for poetry and plays, but even in stories written as prose, the parts that come from spoken traditions need to be important for the writing to be good and work well.

1. A MUNDA SONG: SONG OF BIRTH AND DEATH

My mother, the sun rose

A son was born.

My mother, the moon rose

A daughter was born.

A son was born

The cowshed was depleted;

A daughter was born

The cowshed filled up.

(Translated from the original Mundari)

Word meanings

Depleted: This means to be used up or to become empty; significantly reduced in number or quantity. “The cowshed was depleted” means it became less full of cows.

Filled up: Became full; completely occupied. “The cowshed filled up” means it became full of cows.

Explanation of the above passage—The song describes a mother’s experience. It states that when the sun rose, a son was born to her. It then says that when the moon rose, a daughter was born to her. The song mentions that after a son was born, the cowshed (where cows are kept) became empty or less full. In contrast, it notes that after a daughter was born, the cowshed became full. The birth of a son, however, is linked to the cowshed becoming empty. This clearly means that a daughter is thought of as more valuable than a son. This is likely because, in Munda society, women play a very important part in different money-related, social, and traditional activities.

Note on the Munda Tribe

The Munda tribals live in parts of Jharkhand, West Bengal, Assam, Tripura, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. They are also known as Horohon or Mura, meaning headman of a village. One of the most studied tribal communities of India, they also have an encyclopaedia on them, Encyclopaedia Mundarica (16 Volumes) by Reverend John Baptist Hoffman (1857–1928) and other Jesuit scholars.

The Munda are probably the first of the adivasis to resist colonialism and they revolted repeatedly over agrarian issues. The Tamar insurrection of 1819–20 protested against the break-up of their agrarian system. In their quest to establish Munda Raj and reform their society to enable it to cope with the challenges of time, they organised the famous millennial movement under Birsa Munda (1874– 1901) where their leaders used ‘both Hindu and Christian idioms to create a Munda ideology and worldview’. However, the uprising was quelled by the British.

Word meanings

Tribals: Groups of people who live in traditional communities, often with their own distinct culture, language, and customs, typically in remote areas.

Jharkhand, West Bengal, Assam, Tripura, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa: These are states in India.

Horohon or Mura: Specific names or titles used by the Munda people.

Headman of a village: The main leader or chief of a village.

Encyclopaedia Mundarica: A very detailed book (or set of books, 16 volumes) containing information about the Munda people.

Reverend John Baptist Hoffman: A title (Reverend for a priest) and the name of a person who wrote about the Munda.

Jesuit scholars: Educated people who belong to the Society of Jesus, a Catholic religious order.

Adivasis: Indigenous or original inhabitants of India, often referring to tribal communities.

Colonialism: The control of one country over another, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

Revolted repeatedly: Rebelled or fought back many times.

Agrarian issues: Problems or matters related to farming, land, and agriculture.

Tamar insurrection: A specific rebellion or uprising by the Munda people in the Tamar region.

Protested against: Showed strong disagreement with something.

Break-up of their agrarian system: The destruction or disruption of their traditional way of farming and managing land.

Quest: A long or difficult search for something.

Establish Munda Raj: To set up or create their own Munda rule or kingdom.

Reform their society: To make improvements or changes to their society.

Cope with the challenges of time: To deal successfully with the difficulties that came with changing times.

Millennial movement: A large social or religious movement often based on a belief in a coming golden age or great transformation.

Birsa Munda: A significant leader of the Munda people.

Hindu and Christian idioms: Ways of speaking or common expressions and ideas from Hinduism and Christianity.

Create a Munda ideology and worldview: To form a specific set of beliefs, ideas, and a way of understanding the world unique to the Munda people.

Uprising was quelled: The rebellion or revolt was put down or suppressed by force.

Explanation of the above passage—The Munda tribal people live in areas of Jharkhand, West Bengal, Assam, Tripura, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa. They are also called Horohon or Mura, which means “headman of a village.” They are one of the most studied tribal groups in India. There is even an encyclopedia about them, called Encyclopaedia Mundarica, which has 16 volumes. This encyclopedia was written by Reverend John Baptist Hoffman (who lived from 1857 to 1928) and other Jesuit scholars.The Munda were likely the first of the Adivasi groups to fight against colonialism. They rebelled many times because of problems with farming land. For example, the Tamar rebellion in 1819-20 was a protest against their farming system being broken up. To try and create their own Munda rule and change their society so it could handle new challenges, they started the famous millennial movement. This movement was led by Birsa Munda (who lived from 1874 to 1901). During this movement, their leaders used ideas from both Hinduism and Christianity to form a Munda way of thinking and seeing the world. However, the British put down this uprising.

Note on the Munda Song

Many ceremonies and rituals of the Munda are associated with birth, death and marriage. Living in close harmony with nature, their lives are synchronised with the changing rhythms of nature, the seasons, the rising and setting of the sun and so on, and not by clock time. The selected Munda song is sung to rhythmic folk tunes at the birth of a son or daughter and invariably communicates their close association with nature. Cattle set off to the pastures in the morning and return to their sheds at sundown. The birth of a daughter is associated with a cowshed full of cows and that of the son with its depletion. Clearly the daughter is considered to be a more precious asset than the son. This is probably because, in Munda society, the women have a dominant role to play in the various economic, social and ritual activities.

Word meanings

Ceremonies: Formal events or rituals for a special occasion.

Rituals: A series of actions performed according to a prescribed order, often for religious or traditional purposes.

Associated: Connected with something else.

Synchronised: Happening at the same time or rate; moving or operating together.

Rhythms: A strong, regular, repeated pattern of movement or sound. The natural cycles like seasons or day/night.

Invariably: Always; in every case.

Communicates: Shows or expresses.

Pastures: Fields of grass where animals, like cattle, feed.

Sundown: The time when the sun sets; evening.

Depletion: The act of using up a supply or resource; making something empty or less full.

Precious: Of great value; highly esteemed or cherished.

Asset: A useful or valuable thing, person, or quality.

Dominant: Most important, powerful, or influential.

Economic: Relating to money, trade, industry, and the production of goods and services.

Explanation of the above passage—Many important events and traditions of the Munda people are connected to birth, death, and marriage. Since they live closely with nature, their daily lives match the natural changes in seasons, and the sun’s rising and setting, instead of being set by clock time. The specific Munda song chosen is sung with rhythmic folk music when a son or daughter is born, and it always shows how closely they are linked to nature. Cows leave for grazing fields in the morning and come back to their shelters at sunset. When a daughter is born, it is linked to a cowshed that becomes full of cows. The birth of a son, however, is linked to the cowshed becoming empty. This clearly means that a daughter is thought of as more valuable than a son. This is likely because, in Munda society, women play a very important part in different money-related, social, and traditional activities.

2. A KONDH SONG

This we offer to you.

We can,

Because we are still alive;

If not,

How could we offer at all,

And what ?

We give a small baby fowl.

Take this and go away

Whichever way you came.

Go back, return.

Don’t inflict pain on us

After your departure.

(Translated from the original Kondh)

Word meanings

Offer: To present something (like a gift or sacrifice) to someone.

Fowl: A bird, especially one raised for food, like a chicken or duck.

Departure: The act of leaving a place.

Inflict: To cause something harmful or unpleasant to be experienced by someone.

Explanation of the above passage—The Kondh people state that this is what they are giving to the spirit. They explain that they are able to do so because they are still alive. They then ask how they could give anything at all, and what they could give, if they were not alive. The Kondh people say that they are giving a small baby chicken. They then ask the spirit to take this offering and to leave by the same way it arrived. They tell the spirit to go back and return (from where it came). They request the spirit not to cause pain to them after it has left.

A note on the Kondh Tribe

The term ‘Kondh’ is most probably derived from the Dravidian word, konda, meaning hill. Divided into several segments and distributed over the districts of Andhra Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Orissa, these hill people speak the Kondh language though most of them are bilingual and so conversant with the major language of the state to which they belong.

The Kondh religion is a mixture of the traditional faith of the adivasis and Hinduism. They do not have any dowry system but they do fix a bride price that the groom pays to the bride either in cash or in kind.

Word meanings

Dravidian: Referring to a family of languages spoken mainly in southern India.

Segments: Parts or sections.

Distributed: Spread out over an area.

Bilingual: Able to speak two languages fluently.

Conversant: Familiar with or knowledgeable about something, in this case, a language.

Traditional: Relating to customs or beliefs that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Adivasis: Indigenous tribal communities of India.

Dowry system: A custom where the bride’s family gives money or property to the groom or his family at the time of marriage.

Bride price: A payment (money or goods) made by the groom or his family to the bride’s family before the marriage.

Explanation of the above passage—The term ‘Kondh’ is most probably originated from the Dravidian word, ‘konda,’ meaning hill. Divided into several parts and spread across districts of Andhra Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Orissa, these hill people speak the Kondh language. However, most of them are bilingual, meaning they can speak two languages, and are familiar with the main language of their state. The Kondh religion mixes their traditional tribal faith with Hinduism. They do not have a dowry system. Instead, they set a bride price that the groom pays to the bride, which can be either money or goods.

A Note on the Kondh Song

The Kondhs observe a number of rituals in connection with birth, puberty, marriage and death, with specific folk dances and songs for each occasion. They believe in the existence of gods and spirits, both benevolent and malevolent.

The song here is sung at the death of a person beseeching the spirit of the dead to stop troubling the living. It is based on the Kondh belief that people love their homes so much that their souls are reluctant to leave the hearth even after death. These spirits, though generally kind, can become harmful at times since they are now unable to participate in earthly life. It is, therefore, customary to make generous offerings to the spirit. The song begins by saying that the dead spirit will be able to receive offerings only if the others in the family continue to live and prosper. They reveal their willingness to do anything to make the spirit happy but, in return, the spirit must also promise not to trouble them with its visits.

Word meanings

Rituals: A series of actions or a ceremony performed in a set way, often for religious or traditional purposes.

Puberty: The stage of a person’s life when they become physically able to have children.

Benevolent: Kind and good; wishing to do good.

Malevolent: Evil or harmful; wishing to do harm.

Beseeching: Asking someone urgently and seriously to do something; pleading.

Reluctant: Unwilling and hesitant; not wanting to do something.

Hearth: The area in front of a fireplace, often representing home and family.

Customary: Done or established by custom; usual or traditional.

Explanation of the above passage— Kondh people perform many rituals for birth, puberty, marriage, and death. For each event, they have special folk dances and songs. They believe that gods and spirits exist, and these spirits can be both kind and evil. The specific song mentioned here is sung when someone dies. It asks the spirit of the dead person to stop bothering the living family members. This song comes from the Kondh belief that people love their homes so much that their souls do not want to leave their home’s fireplace (hearth) even after death. These spirits, even though they are usually kind, can sometimes become harmful because they can no longer take part in life on Earth. Because of this belief, it is a custom to give generous gifts to the spirit. The song starts by explaining that the dead spirit will only be able to get these gifts if the other family members stay alive and do well. The family shows they are willing to do anything to make the spirit happy. But, in return, the spirit must also promise not to bother them by visiting.

3. ADI SONG FOR THE RECOVERY OF LOST HEALTH

Oh my beloved one

If you lost your health due to ill luck

I come forward here to save you

With this Emul

To call back your lost health.

Listen to the sound of this sweet ornament

And follow me to your sweet home.

I tie this Ridin creeper

To fasten your soul to your body.

Follow the footprint of this cock

Come, come with me to your home.

(Translated from the original Miri Agom)

Word meanings

Beloved one: the loved nephew or niece who is ill.

Ill luck: Bad fortune or bad luck.

I come forward here to save you: the maternal uncle of the sick person comes forward to perform the ritual for the return of the spirit of good health.

Emul: An amulet; specifically, a healing ornament used in the ritual.